A Reflex Review

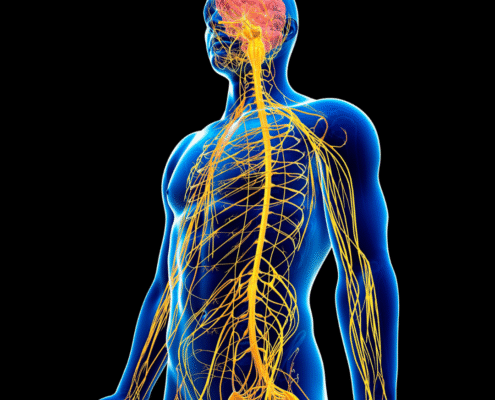

Developmental ReflexesOur reflexes work to support the strengthening of our neural pathways and underpin our daily behavior, an important connection in our reflex integration work. In this more comprehensive review of our early reflexes, we’ll take a look at how immaturities may manifest in potential social, behavioral or even physical challenges as we develop.

Spotlight on Amphibian Reflex

Developmental Reflexes Our Amphibian reflex emerges once several earlier reflexes are integrated and we gain an understanding of the independence of our upper and lower body. Much like cross-lateral movement patterns, the Amphibian reflex enables balance and postural stability for upright movement.

Spotlight on STNR

Developmental Reflexes As a later stage transitional reflex, STNR draws upon integration of earlier reflexes that help reinforce the body’s coordination of upper and lower halves. STNR’s rocking motion supports the understanding that the head can move independent of the body while helping to develop muscle tone and postural stability.

Spotlight on Landau Reflex

Developmental ReflexesThe Landau reflex underpins postural and navigational movement, as well as binocular vision and hearing. As an arousing reflex, where blood flows to the prefrontal cortex when the head tilts, several emotional developments occur with Landau’s integration. Just as the body physically extends to reach out into the word, the reflex underpins self-initiation.

Spotlight on ATNR

Developmental ReflexesAsymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (ATNR) involves a primitive movement pattern that serves to create the first sensory motor connections to the right and left hemispheres leading us to an understanding that we have both a right and left side.

Spotlight on Spinal Galant Reflex

Developmental ReflexesSpinal Galant is a reflex that establishes our ability to move side to side, and subsequently, the ability to move upright with a stable spine. Muscle tone in the lower spine, and stiffness in the lumbar region of the back, impact posture and postural development throughout life.

Spotlight on Tonic Labyrinthine Reflex

Developmental ReflexesThe Tonic Labyrinthine Reflex, or TLR, helps infants establish head control, leading to muscle tone, that supports their independent navigation, from rolling to crawling and learning to walk. The ability to move the head in both directions equally allows for movement with stability.

Spotlight on Babinski Reflex

Developmental ReflexesThe Babinski reflex compliments the Infant Plantar reflex, preparing toes and feet for standing upright with stability. These combined movements guide the development of walking, jumping and even moving laterally as we grow.

Spotlight on Babkin Reflex

Developmental ReflexesThe Babkin Reflex is the opening of the mouth that occurs with a stimulus in the hand. It works in concert with our grasping reflexes and builds upon defensive reflexes that together help us feel safe and secure. Together, these reflexes help to support the foundation for healthy attachment and social behavior.

Spotlight on Palmar and Infant Plantar Grasp

Developmental ReflexesBoth of these grasping movements play a role in cling, the second stage of Moro’s integration. They build a sensation of safety and security in the world, enabling the ongoing development of fine and gross motor skills as reflexes integrate later in life.